CUDA Basics: Understanding Double Buffering

There are numerous great resources (books, blogs, docs) for learning about both the basic and advanced topics in GPU programming (some recommendations can be found here). However, many of them leave out the fundamental optimization techniques that I see are being used over and over again. My intent is to through this series of “CUDA Basics” posts introduce and give an intuitive introduction to various optimization techniques that we employ when writing kernels.

Double buffering is a technique to remove the synchronization required due to write after read race conditions (or similarly, read after write). Intuitively, write after read race conditions can arise in code that should operates in waves and where this wave-like structure is crucial for correctness.

For instance, in the first part of the wave, some data is being read from memory and used in a computation. In the second part of the wave, the data is written back to same memory location, now with updated values. When it’s time for the next wave, we must ensure that the writes from the previous wave have all completed or else we risk reading old data during this wave. This leads to a race condition where you might end up reading either updated or old data.

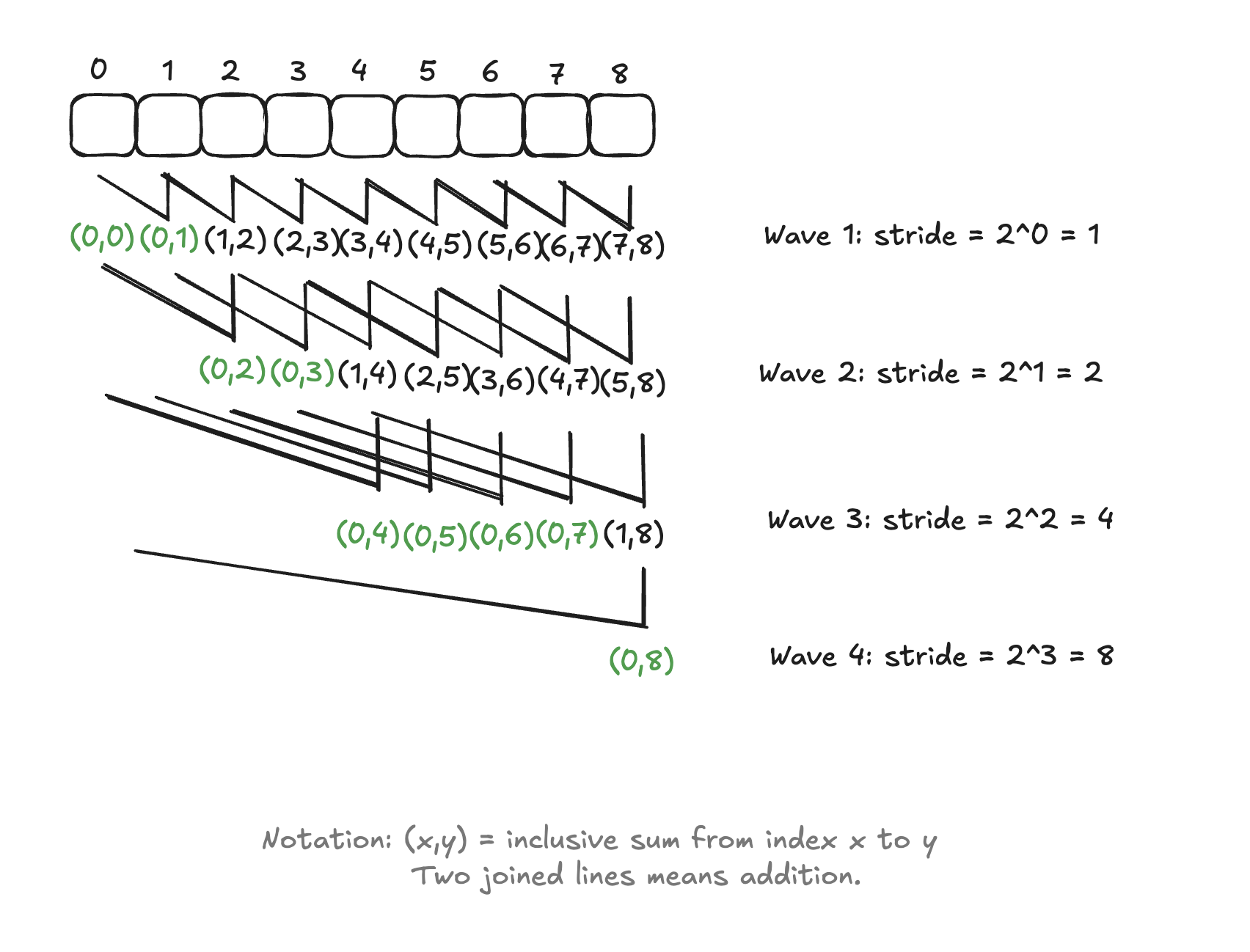

As an example, consider the following computational structure for a very simple implementation of the Kogge-Stone parallel scan algorith:

This algorithm will compute the prefix sum for an array of values in a parallel fashion. As we can see, it uses on a wave-wise logic to iteratively compute the prefix sum for every index in the array. The synchronization required for the correctness of this algorithm should be clear from the image.

The trivial fix for this race condition in CUDA land is to use two barriers __syncthreads(), one before the read in first part of the wave, and one before the write in the second part of the wave.

This ensures that we always read up-to-date values written in the previous wave, and also that we don’t update the memory in the second part of the wave before all threads have completed their read operations.

As you might have anticipated, double buffering is another solution to the write after read issue. But before we get there, let’s consider a real example of two-barrier solution.

Two-barrier solution to write-after-read race conditions

Consider the following simple Kogge-Stone algorithm for parallel scan on a single block of data:

template<typename size_t, const int block_size>

__global__ void inclusive_scan_kernel_kogge_stone_block_local(const size_t *X, size_t *output, const int size, int logical_stride) {

uint gtid = blockIdx.x * block_size + threadIdx.x;

__shared__ float sX[block_size];

// 1. Each thread loads a single element from GMEM

if (gtid < size) {

sX[threadIdx.x] = X[gtid];

} else {

sX[threadIdx.x] = 0.0f;

}

// 2. Main-loop in SMEM

for (uint stride = 1; stride < block_size; stride *= 2) {

__syncthreads();

float acc;

if (threadIdx.x >= stride) {

acc = sX[threadIdx.x] + sX[threadIdx.x - stride];

}

__syncthreads();

if (threadIdx.x >= stride)

sX[threadIdx.x] = acc;

}

// 3. Write back to GMEM

if (gtid < size) {

output[gtid] = sX[threadIdx.x];

}

}

In step 1, we first collaboratively load one element from GMEM into SMEM and pad out-of-bounds entries accordingly.

Step 2 consist of a mainloop where each thread is responsible for computing the cumulative sum up until its index. It does this updating the value at the thread’s index with the value at an index stride to the left in the input array.

Since each thread reads both the value at its own index, and also at a neighboring thread’s index (stride steps away), we cannot directly update the value in SMEM.

Had we done this, we would interfere with the calculation done by the thread stride steps to the right of the current thread, as that one in this iteration of the loop reads the value at the current thread’s index.

Instead we first perform read from SMEM and computation, and store in a register acc. We then issue a __syncthreads to wait for all threads in the block to finish these reads before we write the updated value from registers back into SMEM.

The next iteration of the mainloop then starts with another barrier to ensure that the writes from all threads in the block have finished before go back to reading again. Otherwise we risk reading outdated values from SMEM.

Intuitively these barriers ensure that the kernels run in lock-step. The drawback of this is obviously that we twice per loop iteration must wait for the slowest thread to complete it’s work before any other thread can continue.

Double buffering to the rescue

Double buffering is a simple alternative solution where we use two logical SMEM buffers, and use one of them to read values from (“read buffer”) and the other one to write the new values into (“write buffer”). Once we have completed the writes in one wave, we swap the roles of the two buffers which makes the current “read buffer” into the next wave’s “write buffer”, and vice versa.

This is how the mainloop would now look:

__shared__ size_t sX[2 * block_size]

// Mainloop

for (uint stride = 1, i = 0; stride < block_size; stride <<= 1, ++i) {

__syncthreads();

uint src_offset = block_size * (i % 2);

uint dst_offset = block_size * ((i + 1) % 2);

size_t val = sX[src_offset + threadIdx.x];

if (threadIdx.x >= stride) {

val += sX[src_offset + threadIdx.x - stride];

}

sX[dst_offset + threadIdx.x] = val;

// We need to remember into which buffer we wrote the last values

if (stride * 2 >= block_size)

last_i = i;

}

The main differences vs the first implementation is:

- Shared memory is twice as large. One half is the read buffer, the other half is the write buffer.

- The mainloop tracks another variable

iwhich is incremented in every iteration. It helps us determine if the first part of the buffer is a read or write buffer. - The mainloop only contains a single

__syncthreads. - We read values from the read buffer, and write to the write buffer.

- We swap the role of the read and write buffers in every iteration.

The src_offset and dst_offset computations ensure that one of them has the value 0 and the other block_size, and that these are swapped in every iteration.

Note that this technique assumes you have SMEM to spare so that you don’t reduce the occupancy of your kernel. You can check this in Nsight Compute.

Hopefully this example could provide you with better intuition for when and how double buffering can be used to reduce thread stalling during write-after-read race condition handling.